AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN TURNAROUND: THE UNTOLD STORY OF THE AMERICAN WEREWOLF SEQUEL THAT WASN’T - Part 2

Good News and Bad News

“We handed in the script and were told ‘this is a good news/bad news situation’,” Burns said.

“The good news was they loved our script and, instead of making it a low budget nothing, they wanted to make it a big summer movie. They weren’t looking to make a three million dollar movie any more; they were now looking to make a 25 million dollar movie.”

The bad news? With only one feature under his belt, Stern wasn’t considered a sufficiently bankable big-budget director. A lot had happened since Stern and Burns were hired on ‘American Werewolf in Paris’. The studio behind ‘Freaked’ had shelved the film, dumping it in only a few theatres. (The film would eventually go on to find a devoted, cult audience. However, that was yet to happen.)

“Suddenly my reputation was not that of a hot young director - it was a young director who’d just made a stiff,” Stern said

“Joni (Sighvatsson, one of the owners of Propaganda Films) told me that they were going to interview other directors, that they weren’t sure they wanted me. He told me they needed an A-list director to get the financing in place for the production. But he said he said I should go ahead and come up with a pitch to try and win them over. He even gave me a little money to spend on hiring a storyboard artist and getting some concepts from Alterian and Steve Johnson.”

Stern enlisted the help of Tony Gardner, who’d handled the practical effects duties on ‘Freaked’ - designing such memorable creatures as The Worm, The Sock and Oritz the Dogboy (as memorably played by co-writer/co-director Alex Winter’s ‘Bill and Ted’ co-star, Keanu Reeves).

Gardner, who started his career working for Rick Baker on the John Landis music video for Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’, was excited by the prospect of building on Baker’s iconic work on Werewolf.

“When I worked for him (Baker), I got to see all the stuff from ‘American Werewolf’ up close and personal, which was very inspiring,” Gardner said.

“This (‘Paris’) was a chance to do justice to how innovative Rick is while paying respects to the original - it’s a classic that still holds up. So we wanted to take advantage of advances in technology to do more with those original ideas.”

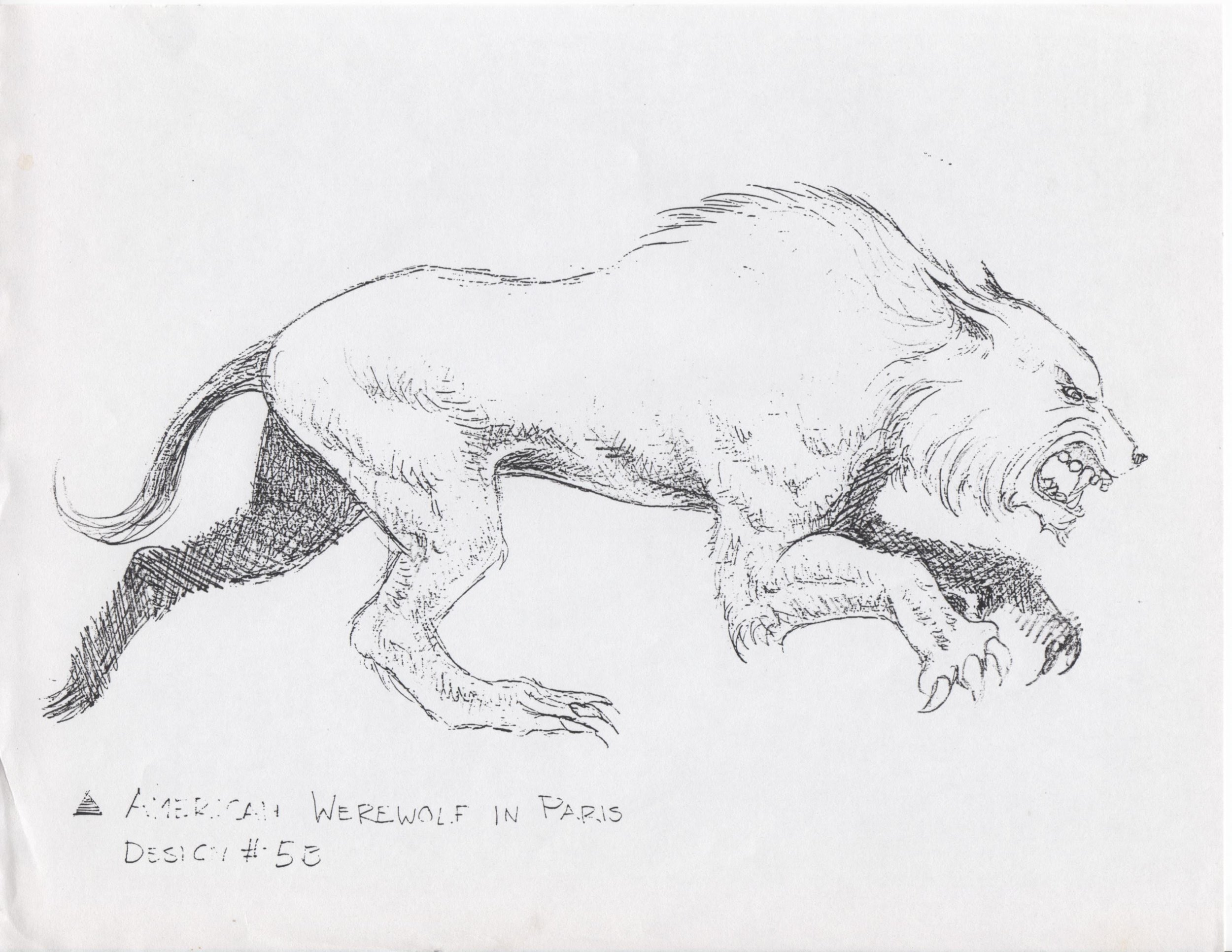

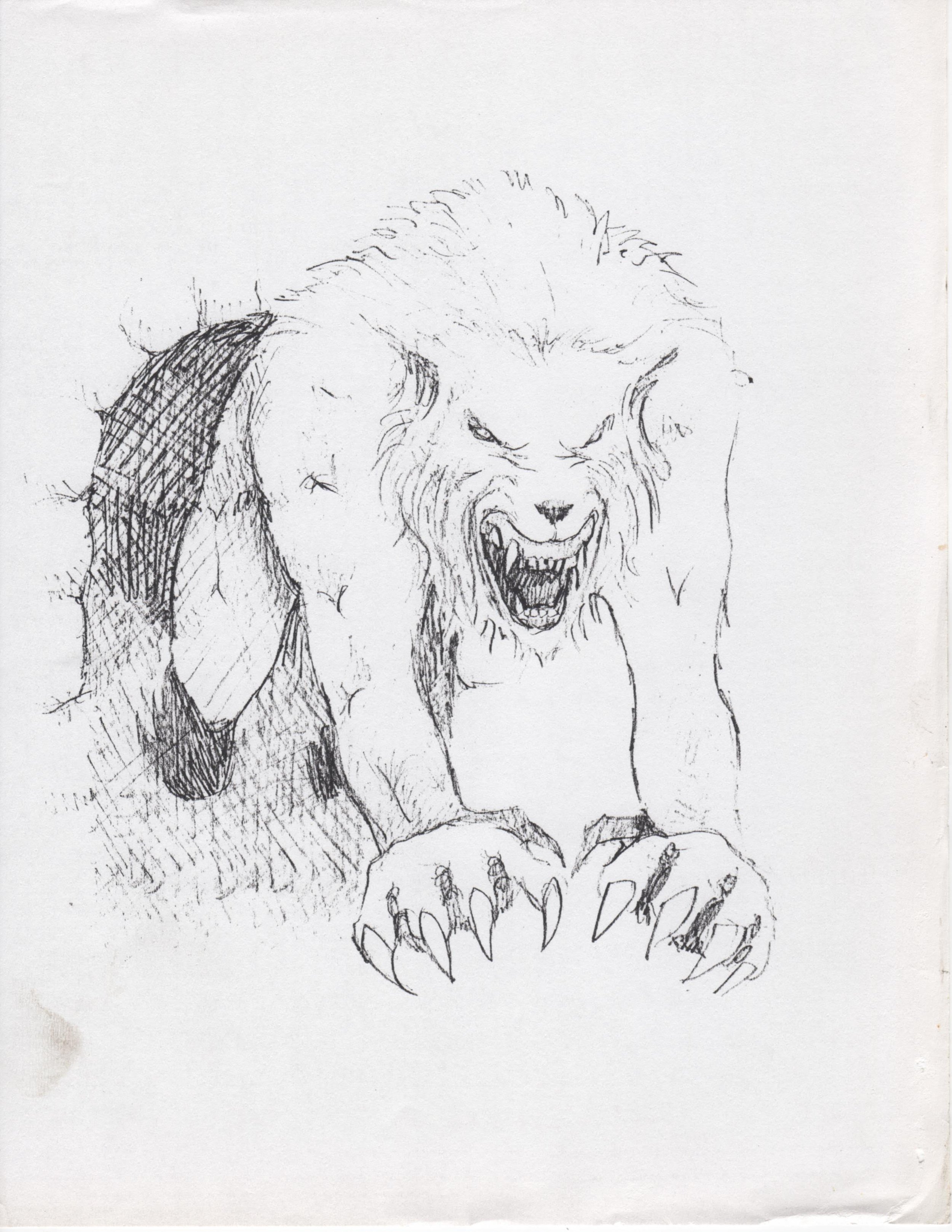

Stern saw the new creature as an integral part of the pitch he’d hoped would help him hold on to the directorial reins.

“I had my personal pet peeve with werewolf movies in general, which is that I always thought the werewolf was a clunky monster because the anatomy of a dog just doesn’t lend itself to a scary humanoid monster,” he said.

“For one thing, dogs have very skinny legs. Other than the mouth and the teeth, they’re not particularly terrifying in terms of their anatomy, and I thought why do we have to do it that way? If you look at the world and the scary kind of predators that exist in the world in general, big cats are more impressive looking visually. So I thought I could sneak in the anatomy of a big cat - in the four limbs and body - because lions have these giant, muscular limbs with big claws, which I thought could be even scarier than the beast that Landis and Rick Baker had done.”

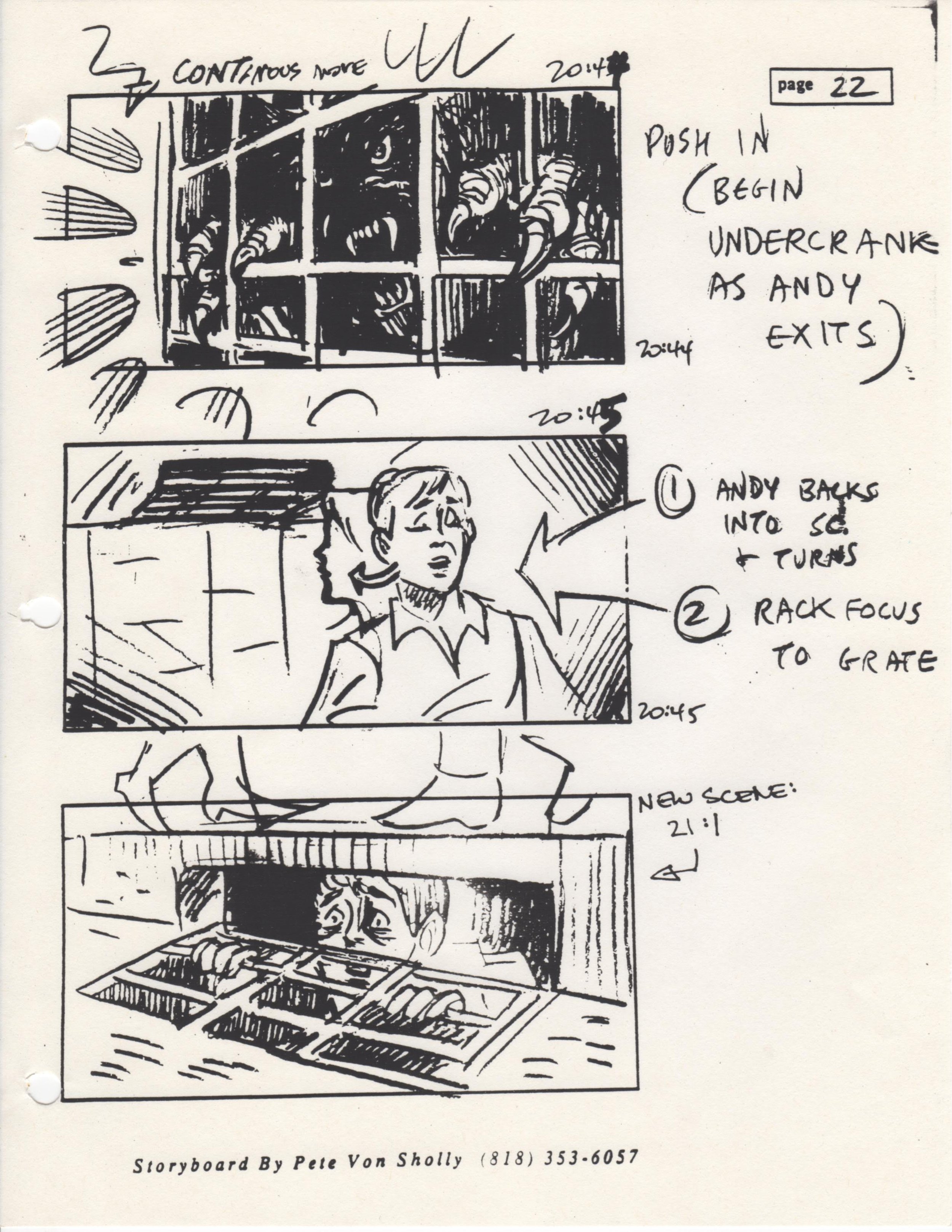

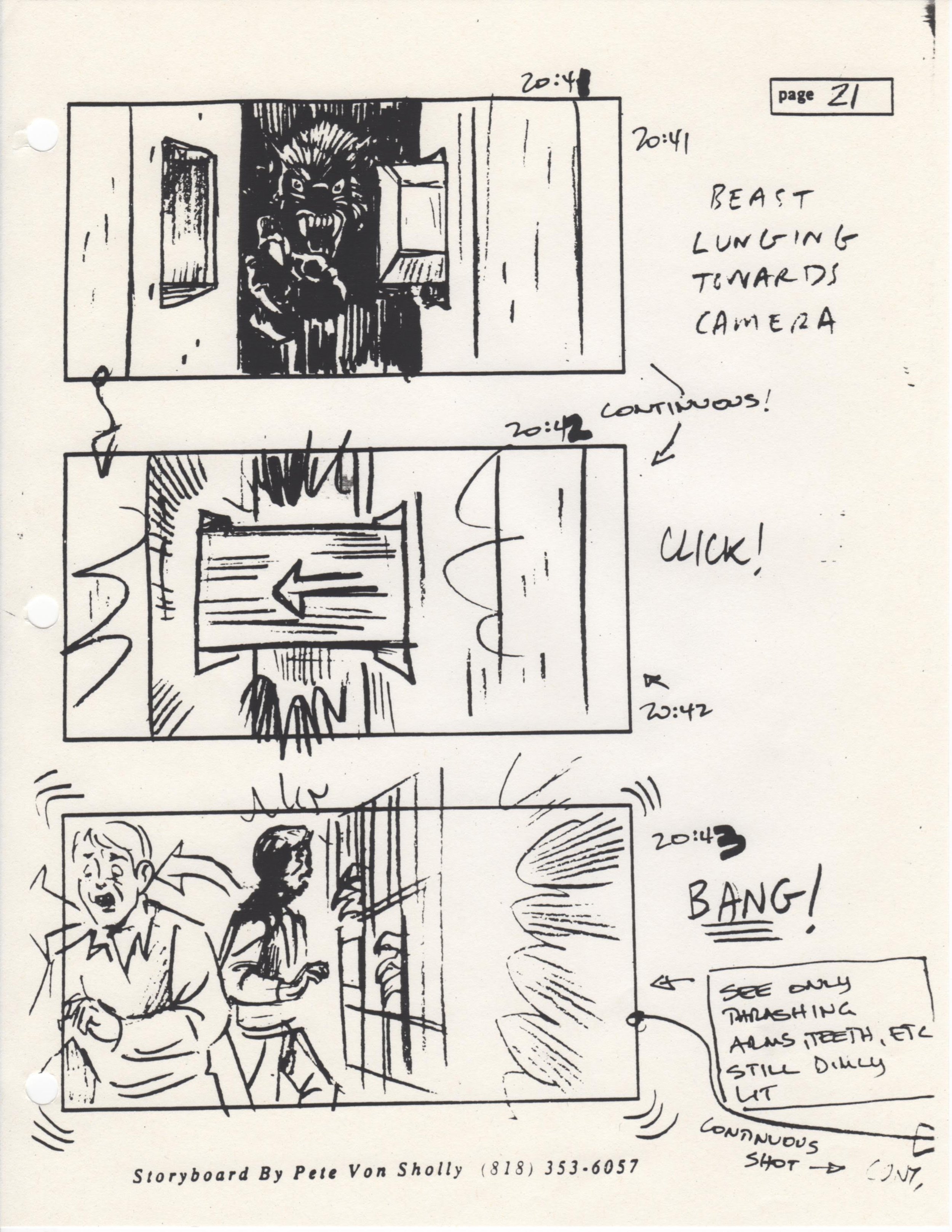

Stern’s pitch took its lead from Phil Tippett’s work on ‘Jurassic Park’ - employing a blend of CGI and practical makeup effects.

“I thought we could use this new technology - especially helped by the dark and shadowy environment I had pictured it in, which would hide a lot of the limitations of the CGI,” he said.

“I thought we could do a cool monster that could sprint at high speeds through these tunnels, instead of staggering awkwardly as you glimpsed it briefly in the original film. I saw it as a combination of special effects makeup with a monster animatronic for the close-ups and then using CGI for running shots.”

Gardner saw the use of CGI - which in the mid-90s was still extremely expensive and nowhere near as advanced as it would subsequently become as a chance to make the creature more agile.

“With CG, we’d be able to have the creature go from being on all fours to standing up on two legs with that animalesque anatomy, as opposed to a man in a suit,” he said.

“The man in the suit would still hold up as the best way to approach everything close up, and the interactions with other people or by using a combination of a guy inside a suit and a rig where the creature’s half of the body would move animatronically. It would mean the creature could interact with people and you could have close-ups you could capture on set without having to try and figure it out in post-production.”

Both Stern and Gardner agree the result, had it gone ahead, would have built on Baker’s work, while providing something fresh and exciting to audiences.

“It seemed like this was an opportunity to merge those two worlds, CGI and more practical effects, together, and create something that nobody at the time had seen before,” Gardner said.

Having nailed down the preliminary details of the creature, Stern felt he was ready to pitch Sighvatsson and his producing partner Steve Golan.

“I had the sculpture (of the werewolf), I had the storyboards done, and I had a pretty good presentation,” he said.

“I made this big, passionate presentation and Steve Golan was basically like ‘well, that’s nice, but there’s no way they’re going to let you direct it. It’s not about your idea. It’s about finding a bankable director whom the foreign investors will accept as bankable’. At that point, I felt really betrayed because I’d done all this work on a presentation only to find out it was pointless, so I was angry, and I think I kind of showed my anger in that meeting, which was probably not a good career move.”

From that point, Stern was out as director. Both he and Burns were still officially attached to the project as writers for the moment - just with a different director at the helm.

A New Direction

With Stern out as director, Tony Gardner - who came in at the eleventh hour to help wow the studio with an innovative new approach to designing the werewolf and his designs were gone as well. For Gardner, it continued his streak of “always a bridesmaid” when it came to werewolf designs.

“At the time, it was really exciting to have an opportunity to be a part of that work and that environment and reality that John Landis and Rick Baker had created,” Gardner said.

“To do that for a new generation felt like it could be something really exciting. There have been a long line of werewolf things that we’d almost worked on that have never happened. It must be destined to not be part of my reality.”

For Stern and Burns, things went rapidly downhill.

A new director was hired - Marco Brambilla, whose career was taking off after the success of the Sylvester Stallone/Wesley Snipes action/sci-fi film ‘Demolition Man’.

“He was the hot action movie director of the day,” Burns said.

Brambilla knew Stern had been sacked as director, making their first (and only) meeting to discuss his vision for the script an awkward - if not downright pointless - exercise.

“There wasn’t any shouting or anything… but it was such a strange feeling,” Burns said.

“We’d been working on this for a year and a half, and put all this thought into it. He’d been on it for a week and was saying ‘I don’t think the ending works’ and ‘this scene’s got to go’.

“Then he asked if a scene - I think it was the big chase sequence from the third act - could go at the beginning.

“I was obstinate, and said something like ‘that’s like asking if you can take the roof off, and put it in the basement. You can do it, but your house will fall over; it just won’t work. It was a farce,” Burns said.

Stern continued; “I remember him saying ‘The script is pretty good, but I think we’ve got to make the villain, like, a supervillain, like totally evil, the ultimate evil. Let’s just crank him up and make him super evil.’ I was just like ‘Oh Christ, this is exactly the wrong idea’. We took pride in writing a villain that was somewhat charming and had a compelling argument because the great villains are the ones that have a great pitch and make you think ‘wow, I can see the logic to this.’ He just wanted a cartoon villain that was twirling his moustache and being all ‘ultimate evil’.”

After the disastrous meeting, it wasn’t long before Stern and Burns found themselves officially off the project altogether.

“For me, it was just like ‘oh, so this is Hollywood, I guess, they like you so much they’ll screw you over’,” Burns said.

“I felt worse for Tom than for me, because he was going to direct it, and he was really looking forward to the chance to show what he could do. Moreover, because he had a contract that said that if they bought our script, he’d direct it, it turned legal.” Burns said.

Stern continued; “It began this process of going through development, and hiring different writers to come up with Marco’s vision which, as soon as the drafts came in, nobody seemed to like. Meanwhile, I had the unfortunate task of trying to work out what to do about the contract I had that said I was directing the movie. I was supposed to get $250,000 to direct it, and they [the studio] were offering me $50,000 as a kill fee to walk away. I told my agent that, since I was getting fired, I at least wanted to get paid what I was contracted to make. I’ll never forget what he said to me - he said ‘Well, Tom. You’re getting fucked. My advice is to lay back and enjoy it.’”

On the strength of that advice, Stern sacked his agent and started looking for lawyers to help him get his money.

“I hired this litigation law firm that were heavy hitters, they weren’t entertainment lawyers, per se. They were scary, heavy duty litigators - they represented countries,” Stern said.

“They told me my contract wasn’t that great, and they thought I had a weak case, but they said they’d give it a try. In the end, Polygram decided just to pay my contract, contingent on the movie getting made.”

However, unbeknownst to Stern, that milestone was still years away.

An American Werewolf in Turnaround

Stern described the time between getting booted off ‘American Werewolf’ and the film eventually entering production as something of a no-mans land.

“There were different directors with different visions, and nobody (at the studio) seemed to like their vision,” Stern said.

Two years after Stern and Burns were kicked off ‘Werewolf’, the studio finally found its director, and principal photography began with Anthony Waller at the helm.

Waller had gained a cult following for his low-budget thriller ‘Mute Witness’.

Also, it was only through the Writers Guild of America arbitration process that Stern and Burns discovered just how many writers were involved in the intervening time.

“Any time you get more than three writers, the Writers Guild has to do an arbitration to determine credit - so we got the arbitration material which listed all the screenwriters that had been involved, most of whose names I knew,” Burns said.

“They (the Guild) sent me a stack of scripts,” Stern said.

"I counted them, and there were 12 writers after we’d been involved, some of them were writing partners, so it wasn’t necessarily 12 drafts, but there were a lot of writers. I was surprised. It was kind of impressive, but my real reaction was ‘Jesus, why can’t any of these writers get it right?’ I was still bitter about it because I was proud of the script we wrote, I thought we really cracked it.”

Burns recalls being somewhat shocked by the level of talent brought in after he’d got the sack.

“I was like ‘Wow! There are Oscar winners here! And this guy wrote the biggest movie of the summer!’,” he said.

"There’s an old saying someone told me in Hollywood - they fire a director when the movie’s in big trouble, and they fire a writer because it’s Monday. These were all lessons I learned after this experience - because I honestly thought ‘We’ve done a great job here, how could it go wrong? Everyone seems excited, what could go wrong with that?’ But, apparently, a lot could go wrong."

The arbitration went in favour of Stern and Burns - with the two securing a writing credit alongside Waller. However, again, Stern and Burns found themselves involved in yet more legal wrangling over money, after the studio failed to send through the writers’ production bonus (a one-off payment to mark the start of production). Eventually, the time came for the duo to view the finished product. Stern, who was living in LA, was invited to the studio to see a rough cut and the finished product for which he received a writing credit bore no resemblance to his vision. Some elements remained intact: Andy’s big werewolf attack takes place near Jim Morrison’s grave, the ‘heart’ cure and the werewolf drug were still crucial plot points, there were Americans, there were werewolves, it was set in Paris, and the character names were the same. Other than that, it was virtually unrecognisable.

Stern was not impressed.

Andy McDermott (Tom Everett Scott) was no longer a regular guy drawn to Paris by the attack on his uncle. Now, he was an American tourist heading to Paris with two of his pals as part of a daredevil’s tour of Europe (each participant getting ‘daredevil points’ for various wild and crazy stunts at different exotic locales, kind of like a pre-Youtube generation version of ‘Jackass’). He meets Serafine (Julie Delpy) as she’s about to commit suicide by jumping off the Eiffel Tower, saving her by bungee jumping off the tower and catching her (“I mean, bungee jumping? It made no sense for the character - not the one we envisioned, and not even for the character as they envisioned it.”). The film then segues into something that felt less like a horror film and more like ‘American Pie’ offcuts, with Andy - now convinced that Serafine is the love of his life - trying to find and then woo her. Badly executed comedy abounded. When the horror finally arrived, the werewolves were now predominantly CGI, and they looked it.

Besides, the werewolf that bit Andy was no longer Serafine, it was the film’s villain, removing the test of character that Burns and Stern had set for McDermott. Oh, and Serafine was now linked to the Landis film - with hints that she was the daughter of Jenny Agutter’s English nurse and her werewolf patient, David Naughton (“It was such a tenuous link! I mean, what was the point?” Stern said).

“I just felt nauseous the whole time,” Stern said.

“The film sucked, it was just a terrible movie.”

Perhaps most disappointingly for Stern, the catacombs that had initially inspired their pitch - and had formed such an integral part of his vision for the film - were nowhere to be seen in the finished product. While several underground sequences remained, they all took place in nondescript, generic tunnels, so bereft of character they could have quickly been shot in a soundstage thousands of miles away. Unlike Stern, Burns didn’t get invited to a screening. Instead, the Canada-based writer had to mooch a ticket to the Toronto premiere.

“I wanted to go see this film that had my name on it, and I couldn’t even get in,” he said.

“But I had a friend who worked at the local TV station who had some free tickets, so he got me in there, and I got to sit there, watch the film and go ‘what the hell is this movie?’ It was bizarre; it was so unrecognisable. I think there were two lines of dialogue of mine left - one was a sex joke where Serafine says something like ‘I’ve had it up to here with you’, and he makes a joke like ‘oh yeah? How far have you had it up with the other guy?’ or something like that. So yeah, after two or three years of work, that’s what survived - the rest, I don’t recognise. It was dispiriting, but - at the same time - when they paid the cheque, it did go a long way to buying my house.”

For Burns, moving on wasn’t too complicated - but for Stern, who’d seen his vision for a scary, funny werewolf film turn into a bloated, poorly-executed mess that still bore his name (albeit only as the writer), it had taken its toll.

Aftermath

“The whole thing was bittersweet - at the time it was hard to know how normal it was… we were new to Hollywood, new to show business,” Burns said.

“We were just like ‘is this how it happens? Did we get royally screwed? Or should I just be thanking the gods that someone made the movie and I got paid?’

“I really couldn’t figure it out at the time.”

Burns primarily works in TV these days, having developed the Disney Channel series ‘My Babysitter’s a Vampire’ - serving as the show’s head writer and co-executive producer. He cites the tone and ‘horror comedy’ world as being a direct descendant of his work on ‘Freaked’ and ‘Werewolf’.

After ‘Werewolf’, Burns said was fortunate to have other development gigs on the horizon and, on the personal front, had just got married… helping to soften the blow, and helping him move forward.

“It was much harder on Tom, mostly because, as a director, I think he felt the impact of ’Freaked’ as a more significant professional setback,” Burns said.

“Then, to have what looked like success snatched away yet again on ‘An American Werewolf in Paris’, it was pretty crushing… he’d put so much work into the visuals and designs.

“He had so much to gain from this (‘Werewolf’).”

Stern’s next attempt to get another feature off the ground, a low-budget horror film called “Bad Pinocchio”, fell apart over a dispute over funding, and the series of work-related battles had taken its toll.

“I went into a horrible, major depressive episode… it was the worst time of my life,” Stern said.

Although Stern was struggling, he was able to secure some work with the help of his old contacts - primarily on TV.

A series of chimp-related movie parodies for the MTV Movie Awards, help land Stern a gig with Jimmy Kimmel and Adam Carolla on their new program ‘The Man Show’.

“I had some friends who were working on Jimmy Kimmel’s pilot, ‘The Man Show’… they loved my chimp thing too - so they hired me to do these chimp things for them,” he said.

“When they got picked up by Comedy Central, Jimmy offered me the job of segment director, which was a lifeline to me - because I was so depressed.

“So then I just became a segment director on ‘The Man Show’ and slowly clawed my way back.”

Stern, who has been working consistently in TV ever since remains hopeful of one day getting that second feature off the ground.

“Like I said, I learned a lot doing ‘Freaked’… and I’m still hoping to do a second film and show that I learned a lot,” Stern said.

“In fact, the thing I’ve just done - which is a serialised show - is essentially a feature film cut into 12 episodes… that was really fun to shoot.”

The series in question is called ‘Golden Revenge’, featuring Luke Wilson as a golden retriever, Ice-T as a bulldog and Natasha Leggero as an alcoholic cat. Stern said it had an Adult Swim tone to it.

“It’s basically ‘Homeward Bound’ meets ‘Kill Bill’ - it’s the story fo three pets who are on a cross-country adventure to get back to their family and kill them.

“So, yeah… that’s where I’m at. I’m good these days.”

While 'An American Werewolf in Paris' met with pretty much unanimous disdain from audiences and critics alike (Rotten Tomatoes has it at a 7 per cent Tomatometer and a 30% audience score), and Stern and Burns' vision for an exciting, scary and funny sequel is dead, the old dog may not be dead yet. John Landis' son, Max, is writing a remake of 'An American Werewolf in London' which he hopes to direct. Whether Landis Jr meets the same fate as Stern and Burns (like he did on, say, 'Bright' or 'Victor Frankenstein') is yet to be seen, but there may still be a reason to stay off the moors for years to come.