Bonus: How Archie Broke The Comics Code

Archie Comics was once the bastion of conservative, wholesome America. Yet to survive as a brand and find a whole new generation of fans, they did something unexpected: they broke the Comics Code writes Maria Lewis.

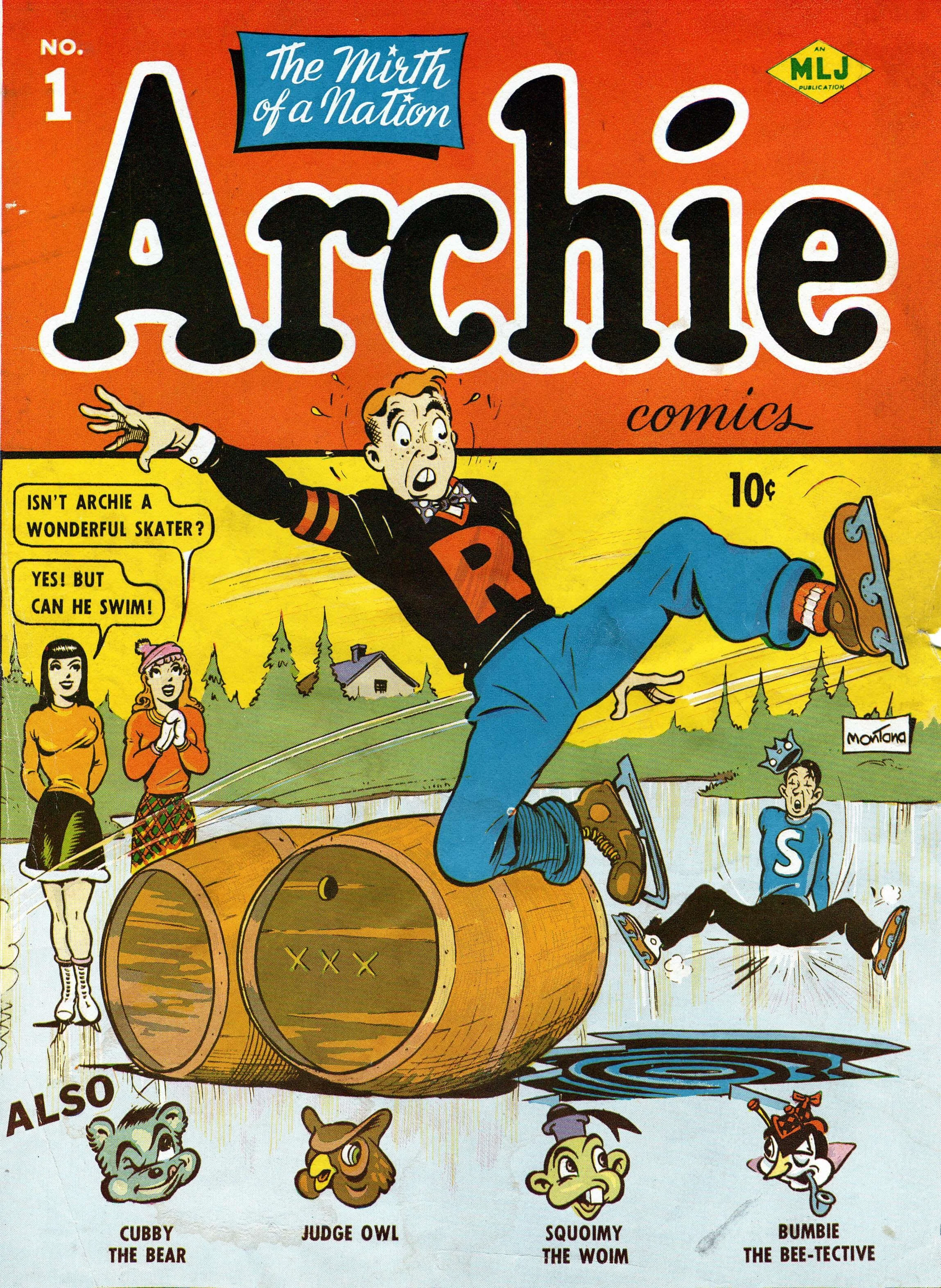

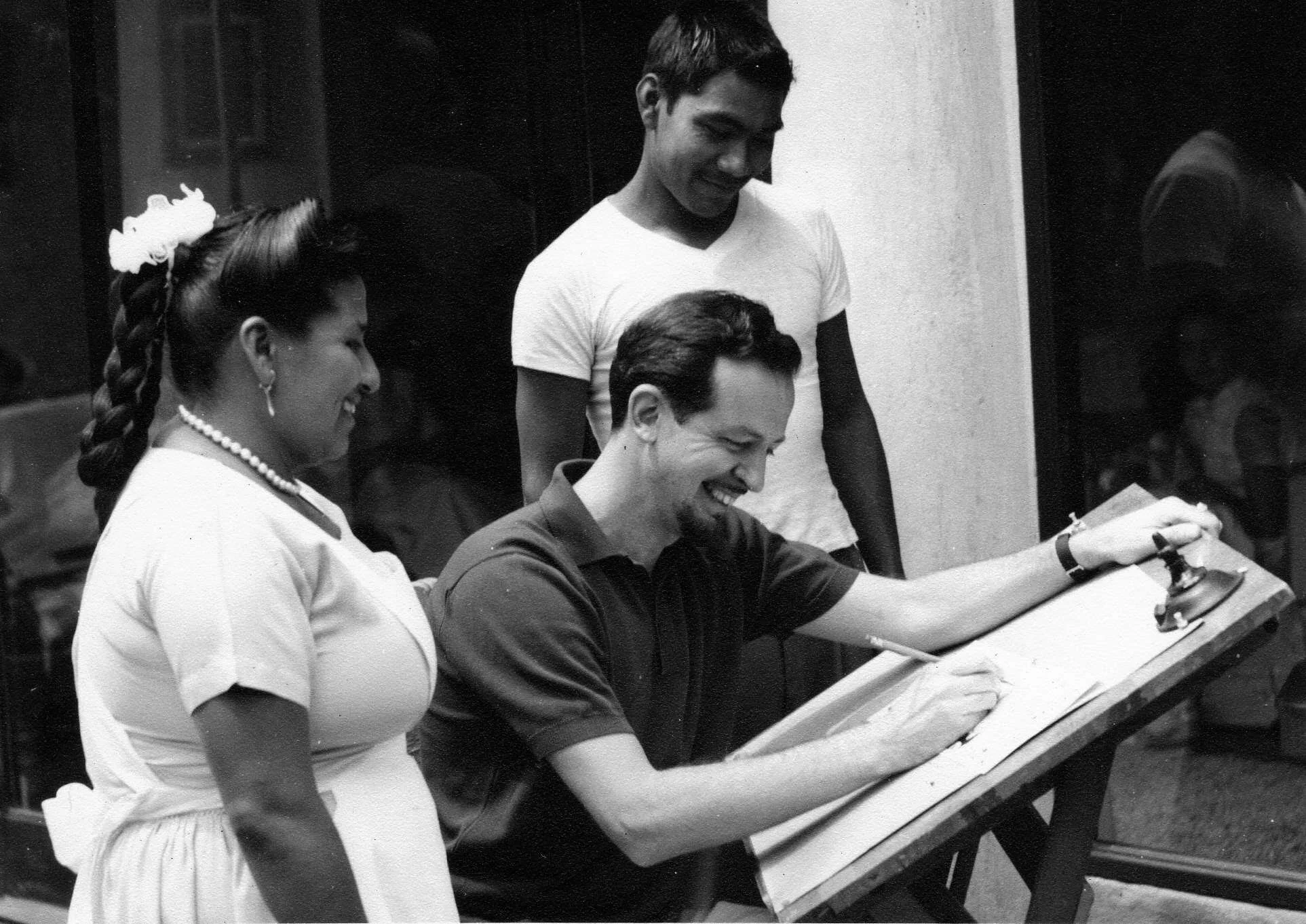

In the late thirties and forties, Archie rose to prominence as one of the staples of a great, American art form: comic books. The creation of Bob Montana – and largely based on his life experiences – and publisher John L. Goldwater, MLJ Comics became Archie Comics and an iconic brand was formed. While Montana passed away in his fifties in 1975 after having a heart attack while cross country skiing, Goldwater went on to run the company for decades. It became somewhat of a family business, with Goldwater’s son – Richard – taking over Archie Comics in the eighties and when he passed, Goldwater’s other son Jonathan picked up from there (for the purposes of clarity we’ll refer to him as Jon Goldwater). “I think the big difference between the two is that Richard came up through the company,” says comic book historian and author of Betty & Veronica: Riverdale’s Leading Ladies Tim Hanley. “John L Goldwater started it, Richard worked at Archie once he was old enough, and was an editor and worked behind the scenes before he took over. So he was really connected to his father’s vision for the company, which was a conservative, wholesome take on Archie.”

In the seventies, that included “evangelical Christian comics” where the characters were licenced out. “John L. Goldwater was huge behind the Comics Code in the fifties to restrict content and to make comics as family friendly as possible,” says Hanley. “The Code is basically Archie’s in-house code with a few tweaks. John L Goldwater was the chairman for over 20 years and Richard kind of carried that on in a lot of ways.” Now we’re getting to the meat of it, because the Comics Code is important and if you think you don’t know what that is, think again. It’s at the opening of one of the greatest superhero movies of all time: Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse. As that game changing opener is starting to roll, one of the things that appears is a stamp that reads: “Approved by the Comics Code Authority” with a weird lil’ ‘A’ glowing in the middle. Before we can talk about how Archie broke the Comics Code, we first need to talk about what the Comics Code was and it’s a long, bendy fucker but in summary … it was cooked.

Brought in in 1954, it was ‘voluntary’ but if publishers didn’t submit their books to the Comics Code Authority, they didn’t get that aforementioned sticker thingy on the front of their books. That could seriously impact whether advertisers decided to advertise inside their comics or not, so it was important from a business perspective. Yet its whole existence was largely due to fear mongering which kicked up after Fredric Wertham's book Seduction Of The Innocent came out the same year the code was introduced. To spare you the read, the general gist of it was a) comics are evil b) they’re corrupting the innocent and c) creating juvenile delinquents. It seems wild in hindsight given that comics are one of the most inventive and boundary pushing mediums today, but in 1954 the whole entertainment industry was being governed by conservative codes designed to protect the moral fibre of the American people.

The Comics Code was based on the worst of ‘em all - the Hays Code - which had been suffocating the motion picture industry for the past 20 years and seen ground-breaking filmmakers like Dorothy Arzner – an openly queer filmmaker who made openly feminist films and was the only female director during Hollywood’s Golden Age – pushed out of the business altogether and into early retirement. “The Motion Picture Production Code was commonly known as the Hays Code after William H. Hays – he was the president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) at the time,” says Chelsey O’Brien, Assistant Curator at the Australian Centre For Moving Image (ACMI) – the most visited moving image museum in the world. “The Hays Code was this self-imposed industry set of guidelines for all the motion pictures that were released between 1934 and 1968 … The code prohibited profanity, suggestive nudity, graphic or realistic violence, sexual persuasions and rape. It had rules around the use of crime, costume, dance, religion, national sentiment and morality. And according to the code - even within the limits of pure love or realistic love - certain facts have been regarded as outside the limits of safe presentation. So basically this means we have a whole lot of married couples sleeping in separate beds for at least 20 years.”

By the time it got to the late sixties - 1968 to be precise – the Hays Code hadn’t been properly enforced for years and it was replaced by the MPAA rating system, which has its own issues and is still used today. The code was extreme and it came in reaction to some key events in the industry following the turn of the century. “Hollywood in the 1920s is a super racy time,” says O’Brien. “Films were beginning to mature, they were dealing with adult content. They were sort of racy and projected images of women in power and making their own choices. There were off-screen stories of drugs and alcohol and partying and over indulgence and then the industry was rocked by really huge scandals: namely the death of Olive Thomas, the murder of William Desmond Taylor, and the alleged rape of Virginia Rappe by popular movie star Roscoe Fatty’ Arbuckle. So all of these things brought really widespread condemnation from religious, civic, and political organisations. Many felt that the movie industry was really morally questionable so there was all this political pressure. I think that with the Hays Code, one of the things the film industry just assumed was that its audience was white and straight and only white, straight males. They would do things that appealed to that audience base, really. So anything that was going to be questioning a woman’s sexuality or women’s sexual preference or even men’s sexual preference, there was this real return to traditional values. A little bit of that is we’re coming out of the Depression, we’re coming out of World War I, so there’s this general American sentiment that is returning to conservatism.”

This ‘return to conservatism’ eventually spread to reading materials as well, literature, comics and … voila, the Comics Code was born. It was a particularly difficult time for horror comics, romance comics, a lot of genre comics, which went underground. Even mainstream comics struggled to stay as wholesome as necessary – like Wonder Woman. It had started as this really progressive, ground-breaking comic for the time when it debuted in 1941. That had a big part to do with its creator – Professor William Marston, inventor of the lie detector test – and the polyamorous relationship he was in with two feminist women, his wife Elizabeth Marston and spouse Olive Byrne, who provided input into the character such as the matriarchal themes and having her wear a skort in those early issues (because fighting in a skirt was impractical, duh). But by the fifties, sixties, and seventies, to pass the Comics Code a lot of those progressive elements had regressed and … well, were some of the worst storylines in Wonder Woman’s nearly 80-year history. But you know what title wasn’t struggling? Archie.

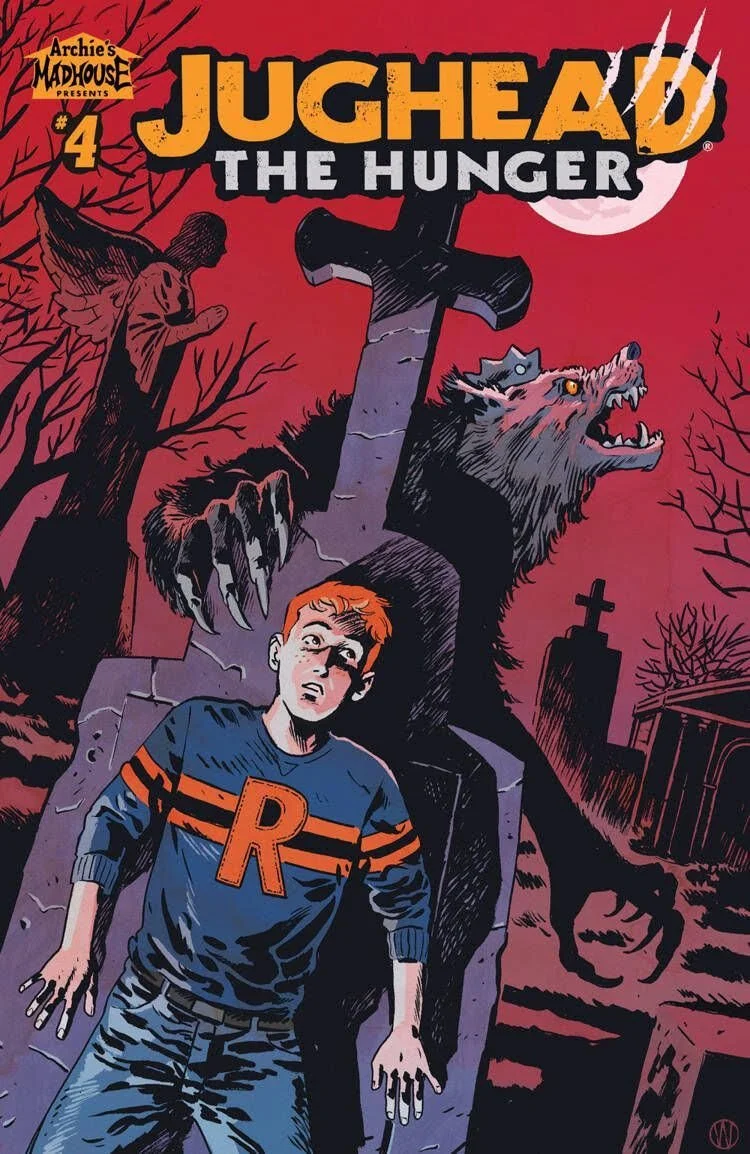

“When I was younger and I first got into Archie, all you had were the classic stories which were very family friendly - they’re kinda sly humour,” says Alex Segura, Co-President of Archie Comics and author. “But as you get older, at least for me as a boy, you want to read more action orientated stuff and Archie didn’t have that then. You got the classic stuff and then you moved on … to things like Spider-Man, X-Men or Superman. But now as a brand Archie runs the spectrum. We have edgy noir stuff like Riverdale, we have horror stuff like Jughead: The Hunger, we have superheroes like The Black Hood. So I feel today, if a fan were to tap into the early classic stuff and get into it, it could then be a bridge to the next thing. That’s not to say we think you’ll only read Archie. All boats rise but I think that variety of content is there now and that’s allowed the brand to continue and stay vibrant … For a point there in the late eighties, early nineties, Archie felt very stuck in place and frozen in time and you got the sense that the stories were in a Pleasantville-type era as opposed to today. When our current CEO Jon Goldwater took over, he made it a point to say these stories needed to seem like they were happening in the real world, they need to have diversity, this is happening now not in the fifties. That really resonated with people, you can see that in the stories. You can tell a classic Archie story that’s funny and entertaining: it doesn’t need to feel like it’s retro.”

By the nineties, the Comics Code was becoming less and less relevant. Marvel stopped following the code in 2001, with other publishers beginning to jump ship and abandon it as well. By the time a new decade hit in 2010, there was only a trio of big wigs still adhering to it: Bongo Comics, DC Comics, and, you guessed it, Archie Comics. And as Tim Hanley explains, the clock was ticking on that. When Jon Goldwater took over in the late naughts, he was entertainment adjacent and had some new, modern perspectives. “He came in and was like ‘you guys are kind of stuck right now, you’ve been doing the same thing for a while and it’s not working’,” says Hanley.” It worked for a long time, but it wasn’t working at this stage: they really had no presence in comic shops relative to other publishers … I think he had a respect for what Archie is, but coming in from the outside he quickly realised this is not sustainable anymore, we need to mix things up.” And things were well and truly mixed: The Married Life debuts where Archie proposes to Veronica, followed by an alternative timeline where he proposes to Betty. Another pivotal moment was the introduction of Kevin Keller, Archie’s first gay character.

“If you want to get Shakespearean with it, Archie basically killed the Comics Code,” says Hanley. “This was under Jon because to do Afterlife With Archie (it) was very not the code, it wouldn’t have been approved. So when Archie finally decided ‘we’re not going to do the code anymore’ it killed the code for everybody. Other publishers were kind of moving away from it, but Archie stepping back and saying ‘even in our regular books we don’t need it anymore’, that killed off the code across the industry. It just disappeared, it was no more all of a sudden because Archie - the last stronghold of family values in the comics industry - decided to pull out of it.” This made way for “cool new things” within the Archie brand. In Afterlife With Archie, the brand enters into a new era and reinvents not only an iconic character but reinvents an iconic brand. That’s something rarely done successfully, let alone done well. It’s one of a dozen modern tales that took readers in a whole new, unexpected direction, incorporating elements of horror, science fiction, romance, exploitation, action and all the best parts of speculative fiction.

It’s this new era that gives us the television series Riverdale, which is a colossal hit, then The Chilling Adventures Of Sabrina The Teenage Witch and now the Katy Keene show. Archie is more popular than ever thanks – in part – to its breaking of the Comics Code. And according to Segura, it’s just the beginning. “I think you’ll continue to see the brand diversify and stay vibrant and do different things,” he says. “You know the TV stuff has been great in terms of awareness and people are so tapped into what Archie is doing, which is huge. And the comics, I think we’re continuing to show that as long as we’re true to these characters and they are who the fans think they are, you can put them anywhere. Archie can fight a zombie apocalypse; Jughead can become a werewolf, we’ve actually got a really fun twisty take on Josie coming soon that we’ll be able to say more as it gets closer. But as long as we take these characters and write them and treat them with respect and do what fans expect in terms of personality and how they behave, you can put them anywhere. That’s where I think you’re seeing a lot of response: you’re seeing it from nostalgic fans who like to see different takes on these characters and you’re seeing it from new fans who like the twist.” From Segura’s perspective, the characters are the hook and new readers – new Archie fans – end up taking a “dive into the mythos, which is great!”

You’d think that perhaps this edgy, new direction would ostracise some of Archie’s traditional audience but according to daughter of Archie creator Bob Montana, Lynn, it’s an exciting time as she has watched the characters and the brand be reinvigorated with a whole new wave of popularity. She also hopes it will be a gateway for a new realm of discovery. “This new millennium of people who are watching Riverdale, I do hope that they take the time to at least go on Amazon and see the books that are there of my dad’s original artwork for the comic strip,” she says. “Because that was very different from the comic books: the comic books were written by a number of bull pen artists who were hired to do comic books. But my dad’s strip … I have always felt it was written for the adults. A lot of his gags and jokes in the comic strip in the newspaper - which is what he did for 35 years basically - you had to be an adult to get some of the jokes because adults were the ones who bought the newspapers, not the kids. Not that kids couldn’t enjoy them, but he wrote them for an older audience to enjoy as well, not just 13-year olds.”

This article is a written version of the Josie and the Podcats bonus episode How Archie Broke The Comics Code. Josie and the Podcats is a limited podcast series hosted by best-selling author, screenwriter and journalist Maria Lewis, and produced by Blake Howard of Michael Mann’s One Heat Minute. New episodes release every Sunday, with bonus episodes during the week.